But what if you wanted to make the actual Gospel narratives live again? is there any way of avoiding 2000 years of "churchy" connotations while re-telling the gospel itself? Many have tried, few have succeeded. One of the best attempts in the 20th century was Dorothy Sayers's Man Born to be King, a series of radio plays broadcast in Britain during World War II and, in my opinion, one of the most moving of all modern re-tellings of the story of Christ. One reason that MBTBK succeeded where most (e.g.) Jesus movies fail is that it was written for a medium (the spoken voice) that avoids many of the pitfalls of over-familiar religious iconography. Even so, there was a lot of controversy at the time over Sayers's "irreverent" portrayal of Christ.

To my mind, Steve Ross's graphic novel Marked, a retelling of the Gospel of Mark, is another worthy attempt. Ross faced the same problem as Lewis and Sayers, with the additional burden of using a medium (line art) that could not avoid decisions about how or whether to re-use any of the conventions of Christian visual art. He dealt with this problem by putting the narrative in a modern-day setting that is yet not simply a portrayal of our world — the government is a quasi-fascistic Big-Brother entity, technology is everywhere, yet demon possession is common, and an exploitative religion works hand-in-glove with the authorities. Hence Ross dispenses with the need to be "historically accurate," while retaining certain features of the Gospel that are narratively important. He also is able to do something you can only do in comics, namely dispense almost totally with rendering background or scenery, foregrounding the action for narrative vitality, the characters moving and speaking most frequently against a white field or with only vaguely sketched buildings or landscape. This enables the story to seem timeless, yet to retain some minimum sense of place. This in itself is not unlike the biblical narrative, in which most action is foregrounded in similar fashion.

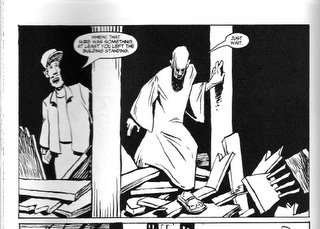

The plot is a combination of faithfulness to the overall shape of Mark's gospel combined with considerable freedom in details. As in the gospel, there is no nativity story, and the book ends as abruptly as Mark does (without the interpolated longer ending), with a resurrection but no resurrection appearances. His choice of "look" for Jesus is interesting. The traditional appearance is gone, replaced by a bald, vaguely Asian-looking guy. I like it. This panel is in the aftermath of the cleansing of the temple:

Actually, the Jesus-classic look does make an appearance later on, but as the aspect of Barabbas. I'm not sure what this is meant to convey; perhaps nothing more than Ross's desire to stand things on their heads. He plays around with traditional iconography without actually using it, or using it in different ways. At the Last Supper we are shown the interior of Jesus' cup, and it looks like the Host floating in a cup of wine. But the next panel shows us that it's the moon's reflection:

In the panels that follow, the cup falls and breaks while Jesus is arrested and beaten, while the moon continues to shine. There is nothing else besides this symbolism to correspond to the Words of Institution.

Ross also uses other icons that have some resonance, non-religious ones employed in religious ways. For instance, here is a scene from the Transfiguration, Jesus with Moses and Elijah.

And I don't think I'm too far off in seeing this trio not simply as Christ, Moses, and Elijah, but also Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Less effective is his employment of a clown — kind of a creepy one — as the angel at the tomb.

There is an interesting review and interview with Ross here at the SBL Forum. It reveals that Ross is an Episcopalian of the modernist variety, one among (regrettably) many in our denomination who seem to believe that the most valuable part of the catechism is the questions. This may account for the fact that his overall portrait of Jesus is lacking something commanding, authoritative, and royal — the Messiah of Marked doesn't quite understand what's happening to him. Not the impression one gets from the actual Gospel. But in general I really like what he's done, and the achievement, taken as a whole, is fresh and appealing. It has the potential to sneak past a lot of prejudice against the gospel narrative and set it before modern eyes as a story of Something new breaking into a world sadly in need of redemption.

1 comment:

Ed, thank you for your review. I have been carrying my copy around to try and find time to write a review myself. You and Dan Clanton have saved me the trouble of covering a lot of the detail. :-)

I will note here, however, that I agree with your account of the weaknesses and I am afraid my review will take those up. In particular that while appreciate greatly the effort and the "freshness" this Jesus does not seem to be offering the world the redemption that you rightly point out it needs. A discussion of repentance of sin, for example, is markedly lacking until we get to the four men lowering their friend on the cot (what is with the eastern European schtick?). As a result, John the Baptist not only looks like a crazy man (I quite like his depiction of JB and of how he receives his prophecy via a pay phone), but his baptizing has no explanation thus he really seems to be crazy, dunking people for no reason!

But I need to simply write my own review... :-)

Post a Comment