A recent conversation in our house:

WIFE: Ha ha, some people are looking at the Mideast troubles and predicting the end of the world.

SELF: I wish.

WIFE: What?! You wish it were the end of the world?!

SELF: Do I wish for the consummation of human history, a new heavens and a new earth, the return of Our Lord? You bet I do.

WIFE: But I'm working on my doctorate.

"The artifex verborum of the dream ... was no less adept than the waking Coleridge in the metamorphosis of words." — John Livingston Lowes, The Road to Xanadu.

Observations on language (mostly ancient), religion, and culture.

By Edward M. Cook, Ph.D.

Friday, July 28, 2006

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

The Seated Teacher

While reading Peter Brown's biography Augustine of Hippo, I was struck by this passage describing Augustine the preacher:

I surmise that the same practice lies behind Matthew's description in the Sermon on the Mount: "Seeing the crowds, he went up on the mountain, and when he sat down, his disciples came to him" (Matt. 5:1). We are to imagine Christ sitting on the mount, teaching, while his disciples stand and listen, at a slightly lower elevation.

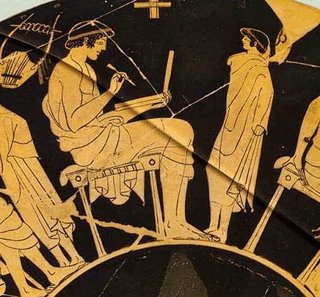

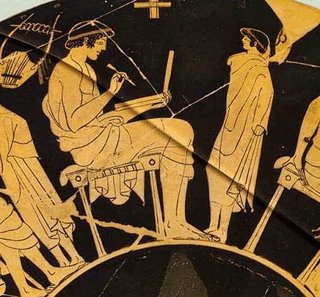

The practice was ancient. Compare these pictures: the first from the Hammurapi stele of the 2nd millennium BCE (which portrays the seated god Shamash instructing a standing Hammurapi in the ways of justice) and a Greek vase, more than 1500 years later (which portrays a student standing before his teacher, who is consulting alaptop folding tablet).

Augustine would not even have been physically isolated from his audience, as a modern preacher would be, who stands in a pulpit above a seated congregation. The congregation of Hippo stood throughout the sermon, while Augustine usually sat back in his cathedra. The first row, therefore, would have met their bishop roughly at eye level, at only some 5 yards' distance.This reminded me that the lecturer, preacher, or teacher of ancient times often sat while his audience stood, which sheds light on the passage in Luke 4:20, which describes Jesus sitting down after reading the scripture: "Rolling up the scroll, he handed it back to the attendant and sat down, and the eyes of all in the synagogue looked intently at him." He was sitting down in the teacher's seat, which would have been elevated (like the bishop's cathedra of Augustine's time, centuries later), while his auditors stood.

I surmise that the same practice lies behind Matthew's description in the Sermon on the Mount: "Seeing the crowds, he went up on the mountain, and when he sat down, his disciples came to him" (Matt. 5:1). We are to imagine Christ sitting on the mount, teaching, while his disciples stand and listen, at a slightly lower elevation.

The practice was ancient. Compare these pictures: the first from the Hammurapi stele of the 2nd millennium BCE (which portrays the seated god Shamash instructing a standing Hammurapi in the ways of justice) and a Greek vase, more than 1500 years later (which portrays a student standing before his teacher, who is consulting a

Friday, July 07, 2006

Vermes on the Qumran Concordance

There is not really much drama in the editing of a concordance, but Geza Vermes puts his finger on an important aspect of the recently published Dead Sea Scrolls Concordance. In the course of reviewing said volume, he rehearses the history of Scroll concordances, and mentions the important card-index concordance put forth by John Strugnell in 1988. This privately photocopied book was not meant to be used outside the circle of original Scroll editors and their students. However:

I don't know if Marty Abegg has any sense of sweet revenge, but I'm glad to see Vermes reminding people of how much Marty and his trusty computer have meant to the history of Qumran studies.

Vermes's verdict on the Concordance: "an outstanding achievement ... truly indispensable." It's always nice to hear such kind words about a project in which one has participated.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Vermes's review appears in Journal of Jewish Studies 57 (Spring 2006), 177-179.

Not only did "illegal" copies circulate among scholars (I received one myself), but as those familiar with the history of Qumran studies well know, an "official" copy of the Concordance, deposited in the library of Hebrew Union College Cincinnati by Strugnell, instead of being kept under lock and key, accidentally found its way to the open shelves and was noticed there by the renowned Talmudist Ben Zion Wacholder. He and a computer-savvy graduate student of his realised that from the concordance it was possible to reconstruct the underlying texts. Their work published in September 1991 ... was the first major breach on the embargo rule imposed on the unpublished manuscripts by the original chief editor Roland de Vaux, and maintained by his successors. The Cincinnati coup was a major contributory factor in the so-called "liberation" of the Qumran scrolls in October 1991. And the name of the graduate student, without whose computer expertise the venture would not have succeeded and who at one stage was threatened with legal proceedings, is none other than Martin G. Abegg, the editor of the present work under review. No revenge could have been sweeter.

I don't know if Marty Abegg has any sense of sweet revenge, but I'm glad to see Vermes reminding people of how much Marty and his trusty computer have meant to the history of Qumran studies.

Vermes's verdict on the Concordance: "an outstanding achievement ... truly indispensable." It's always nice to hear such kind words about a project in which one has participated.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Vermes's review appears in Journal of Jewish Studies 57 (Spring 2006), 177-179.