Fr. Edward T. Oakes has a review here of a new book by Garry Wills, What Jesus Meant, which sounds interesting. I refer to Wills's book, not the sour review, which uses "crypto-Anglican" as a swear-word. Sounds like a compliment to me!

I've always liked Wills, and I particularly commend his Under God: Religion and American Politics. It sounds to me like Fr. Oakes finds Wills's Christianity a little too "mere" and not Catholic (i.e., not papist) enough. But I'm glad to see that GW's theology has not moved leftwards at the same rate as his politics. If he (GW) wants to move over to Episcopalianism, we could use his help.

"The artifex verborum of the dream ... was no less adept than the waking Coleridge in the metamorphosis of words." — John Livingston Lowes, The Road to Xanadu.

Observations on language (mostly ancient), religion, and culture.

By Edward M. Cook, Ph.D.

Tuesday, February 28, 2006

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

Girlish Confusion

Thanks to Targuman for this notice about Israel Drazin's version of Targum Onkelos. I have to mention that this paragraph mystifies me:

If Rabbi Drazin expects people to pay attention to his book because of this kind of tittle-tattle, I imagine he is in for a disappointment.

As Rabbi Drazin explained, Onkelos casts a light on the proper translation of texts elsewhere in the Bible. Thus in rendering Exodus 2:8, the ancient translator refers to Moses' sister Miriam as an almah, which Onkelos translates as "girl." The word is significant to Christians because Isaiah 7:14 speaks of an almah who "will become pregnant and bear a son"—a verse that Christians, rendering almah as "virgin," understand as referring to the Virgin Birth.Wha'? Onkelos is written in Aramaic, the Hebrew Bible is written in, well, Hebrew. The word that Onkelos uses in Exodus 2:8 is uleymta, meaning "girl" in Aramaic, while the Hebrew text has almah. The word uleymta is the common word for "girl" in the dialect of Onkelos (it also commonly translates na'arah "girl, lass"), while almah is rather rare in Hebrew. and its exact nuance is disputed. Although the two words are cognates, this has no bearing on the meaning of any text in which almah appears, except as confirming that Onkelos (and Jonathan in Tg. Isa. 7:14) thought that almah meant "girl" in those texts. For what it is worth, Onkelos translates Hebrew betula, "virgin," by uleymta in Deut. 32:25. Nothing very conclusive comes out of all this.

If Rabbi Drazin expects people to pay attention to his book because of this kind of tittle-tattle, I imagine he is in for a disappointment.

Sunday, February 19, 2006

Here and There

—There has appeared an interesting list of "100 best first lines from novels" here, and, in response, a list of "best last lines." I'll give it some thought, but I'm not sure I could better the first list (the second is still growing). I think I might add the opening sentence of Raymond Chandler's The Long Goodbye: "The first time I laid eyes on Terry Lennox he was drunk in a Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith outside the terrace of the Dancers." And I would certainly add, from Tom Sawyer:

—I finished my review of Ursula Schattner Rieser's L'araméen des manuscrits de la mer Morte. I am told that it will appear in the August 2006 issue of Journal for the Study of Judaism.

—I wanted to give a shout-out to Danny Zacharias for producing a nifty Unicode keyboard for Hebrew transliteration, available here. I used it in producing the review mentioned above; worked like a charm. Thanks, Danny.

"Tom!"It's not a novel, but "Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres" from Caesar's Gallic War is a pretty famous opening.

No answer.

"Tom!"

No answer.

—I finished my review of Ursula Schattner Rieser's L'araméen des manuscrits de la mer Morte. I am told that it will appear in the August 2006 issue of Journal for the Study of Judaism.

—I wanted to give a shout-out to Danny Zacharias for producing a nifty Unicode keyboard for Hebrew transliteration, available here. I used it in producing the review mentioned above; worked like a charm. Thanks, Danny.

Sunday, February 12, 2006

Comic Books (ii): Marked

A while back I wrote about C. S. Lewis's expressed desire to write something about the Gospel story that avoided its "stained glass associations," in order to hear it fresh again. Most people would think, I imagine, that he succeeded in the Narnian Chronicles, at least partly by creating an entirely new world in which to place the story.

But what if you wanted to make the actual Gospel narratives live again? is there any way of avoiding 2000 years of "churchy" connotations while re-telling the gospel itself? Many have tried, few have succeeded. One of the best attempts in the 20th century was Dorothy Sayers's Man Born to be King, a series of radio plays broadcast in Britain during World War II and, in my opinion, one of the most moving of all modern re-tellings of the story of Christ. One reason that MBTBK succeeded where most (e.g.) Jesus movies fail is that it was written for a medium (the spoken voice) that avoids many of the pitfalls of over-familiar religious iconography. Even so, there was a lot of controversy at the time over Sayers's "irreverent" portrayal of Christ.

To my mind, Steve Ross's graphic novel Marked, a retelling of the Gospel of Mark, is another worthy attempt. Ross faced the same problem as Lewis and Sayers, with the additional burden of using a medium (line art) that could not avoid decisions about how or whether to re-use any of the conventions of Christian visual art. He dealt with this problem by putting the narrative in a modern-day setting that is yet not simply a portrayal of our world — the government is a quasi-fascistic Big-Brother entity, technology is everywhere, yet demon possession is common, and an exploitative religion works hand-in-glove with the authorities. Hence Ross dispenses with the need to be "historically accurate," while retaining certain features of the Gospel that are narratively important. He also is able to do something you can only do in comics, namely dispense almost totally with rendering background or scenery, foregrounding the action for narrative vitality, the characters moving and speaking most frequently against a white field or with only vaguely sketched buildings or landscape. This enables the story to seem timeless, yet to retain some minimum sense of place. This in itself is not unlike the biblical narrative, in which most action is foregrounded in similar fashion.

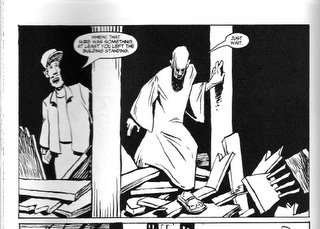

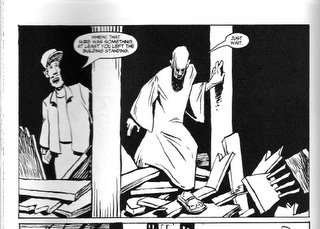

The plot is a combination of faithfulness to the overall shape of Mark's gospel combined with considerable freedom in details. As in the gospel, there is no nativity story, and the book ends as abruptly as Mark does (without the interpolated longer ending), with a resurrection but no resurrection appearances. His choice of "look" for Jesus is interesting. The traditional appearance is gone, replaced by a bald, vaguely Asian-looking guy. I like it. This panel is in the aftermath of the cleansing of the temple:

Actually, the Jesus-classic look does make an appearance later on, but as the aspect of Barabbas. I'm not sure what this is meant to convey; perhaps nothing more than Ross's desire to stand things on their heads. He plays around with traditional iconography without actually using it, or using it in different ways. At the Last Supper we are shown the interior of Jesus' cup, and it looks like the Host floating in a cup of wine. But the next panel shows us that it's the moon's reflection:

In the panels that follow, the cup falls and breaks while Jesus is arrested and beaten, while the moon continues to shine. There is nothing else besides this symbolism to correspond to the Words of Institution.

Ross also uses other icons that have some resonance, non-religious ones employed in religious ways. For instance, here is a scene from the Transfiguration, Jesus with Moses and Elijah.

And I don't think I'm too far off in seeing this trio not simply as Christ, Moses, and Elijah, but also Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Less effective is his employment of a clown — kind of a creepy one — as the angel at the tomb.

There is an interesting review and interview with Ross here at the SBL Forum. It reveals that Ross is an Episcopalian of the modernist variety, one among (regrettably) many in our denomination who seem to believe that the most valuable part of the catechism is the questions. This may account for the fact that his overall portrait of Jesus is lacking something commanding, authoritative, and royal — the Messiah of Marked doesn't quite understand what's happening to him. Not the impression one gets from the actual Gospel. But in general I really like what he's done, and the achievement, taken as a whole, is fresh and appealing. It has the potential to sneak past a lot of prejudice against the gospel narrative and set it before modern eyes as a story of Something new breaking into a world sadly in need of redemption.

But what if you wanted to make the actual Gospel narratives live again? is there any way of avoiding 2000 years of "churchy" connotations while re-telling the gospel itself? Many have tried, few have succeeded. One of the best attempts in the 20th century was Dorothy Sayers's Man Born to be King, a series of radio plays broadcast in Britain during World War II and, in my opinion, one of the most moving of all modern re-tellings of the story of Christ. One reason that MBTBK succeeded where most (e.g.) Jesus movies fail is that it was written for a medium (the spoken voice) that avoids many of the pitfalls of over-familiar religious iconography. Even so, there was a lot of controversy at the time over Sayers's "irreverent" portrayal of Christ.

To my mind, Steve Ross's graphic novel Marked, a retelling of the Gospel of Mark, is another worthy attempt. Ross faced the same problem as Lewis and Sayers, with the additional burden of using a medium (line art) that could not avoid decisions about how or whether to re-use any of the conventions of Christian visual art. He dealt with this problem by putting the narrative in a modern-day setting that is yet not simply a portrayal of our world — the government is a quasi-fascistic Big-Brother entity, technology is everywhere, yet demon possession is common, and an exploitative religion works hand-in-glove with the authorities. Hence Ross dispenses with the need to be "historically accurate," while retaining certain features of the Gospel that are narratively important. He also is able to do something you can only do in comics, namely dispense almost totally with rendering background or scenery, foregrounding the action for narrative vitality, the characters moving and speaking most frequently against a white field or with only vaguely sketched buildings or landscape. This enables the story to seem timeless, yet to retain some minimum sense of place. This in itself is not unlike the biblical narrative, in which most action is foregrounded in similar fashion.

The plot is a combination of faithfulness to the overall shape of Mark's gospel combined with considerable freedom in details. As in the gospel, there is no nativity story, and the book ends as abruptly as Mark does (without the interpolated longer ending), with a resurrection but no resurrection appearances. His choice of "look" for Jesus is interesting. The traditional appearance is gone, replaced by a bald, vaguely Asian-looking guy. I like it. This panel is in the aftermath of the cleansing of the temple:

Actually, the Jesus-classic look does make an appearance later on, but as the aspect of Barabbas. I'm not sure what this is meant to convey; perhaps nothing more than Ross's desire to stand things on their heads. He plays around with traditional iconography without actually using it, or using it in different ways. At the Last Supper we are shown the interior of Jesus' cup, and it looks like the Host floating in a cup of wine. But the next panel shows us that it's the moon's reflection:

In the panels that follow, the cup falls and breaks while Jesus is arrested and beaten, while the moon continues to shine. There is nothing else besides this symbolism to correspond to the Words of Institution.

Ross also uses other icons that have some resonance, non-religious ones employed in religious ways. For instance, here is a scene from the Transfiguration, Jesus with Moses and Elijah.

And I don't think I'm too far off in seeing this trio not simply as Christ, Moses, and Elijah, but also Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Less effective is his employment of a clown — kind of a creepy one — as the angel at the tomb.

There is an interesting review and interview with Ross here at the SBL Forum. It reveals that Ross is an Episcopalian of the modernist variety, one among (regrettably) many in our denomination who seem to believe that the most valuable part of the catechism is the questions. This may account for the fact that his overall portrait of Jesus is lacking something commanding, authoritative, and royal — the Messiah of Marked doesn't quite understand what's happening to him. Not the impression one gets from the actual Gospel. But in general I really like what he's done, and the achievement, taken as a whole, is fresh and appealing. It has the potential to sneak past a lot of prejudice against the gospel narrative and set it before modern eyes as a story of Something new breaking into a world sadly in need of redemption.